| |

|

Paper

Trails: Port Cities in the Classical Era of World History

Marc Jason Gilbert

North Georgia College and State University |

|

| |

|

|

Port cities are a staple of world history. They

are hubs of world commerce and also of regional trade between coast and

hinterland. They are facilitators of both immigration and emigration.

They are transit points for the spread of disease as well as goods and

people. They are also markers of patterns of colonialism and development.

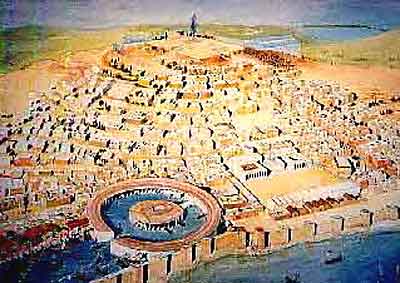

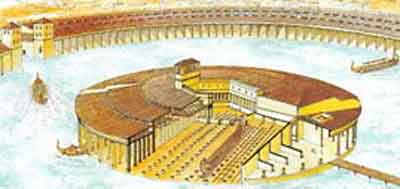

The capitals of most developing countries betray their colonial roots,

having ports as their capital and/or largest cities that today remain

the loci of virtually all post-colonial national administrative, educational,

and medical institutions. They are prime drivers of urban sprawl and slums

as well as economic growth. Yet, the tolerant, permissive and multicultural

atmosphere of port cities in developing as well as developed societies

also make them rich centers of world culture, from break-dancing in Douala

to high rise living in Singapore and Shanghai, to the literature generated

by Alexandria (Lawrence Durrell's The Alexandria Quartet), Mumbai

(Salman Rushdi's Satanic Verses, Manil Suri's The Death of Vishnu)

and Saigon (Grahman Greene's The Quiet American and Margurite Duras'

The Lover), among others. Indigenous cultures often arise from

sea entrepots (the Swahili ports of East Africa), are often transformed

by them (British Calcutta) or end there (Powhattan's New York). Moreover

port cities come in many forms other than coastal enclaves: Phoenix's

Sky Harbor reminds us that airports are also ports of call in analytical

terms. The landlocked harbors of Lothal in India and Bawtry in Yorkshire

remind us that even in historic times changes in coastlines and sea levels

have varied sufficiently to affect human activity. |

1 |

|

So integrated into world historical processes are

the lore of ports of call that they represent one of the few subjects that

one can entrust to Wikipedia for background information and to amazon.com

for relevant scholarship. Merely googling "third world cities" garners the

indispensable work of the same title edited by John D. Kasarda and Allan

M. Parnell (1992); while googling "port cities, Third World" locates John

Middleton's review of Michael Pearson's "Port Cities and Intruders:

The Swahili Coast, India, and Portugal in the Early Modern Era" in

the Journal of World History, 11:1 (Spring 2000): 126-129. Richard

Pankhurst offers an online study of the sea commerce of ancient and medieval

Arabia, Ethiopia and the horn of Africa at http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2002/07/26-07-02/History.htm.

Allen D. Furford provides a lexicon for ancient ports and identifies a number

of them from Japan to Bermuda at http://www.seanet.com/~julie321/seaports.html.

The ancient ports of Sri Lanka are closely studied at http://www.lankalibrary.com/geo/ancient/ancient_ports2.htm,

while Abdera in Thrace is noted at http://www2.rgzm.de/Navis2/Home/HarbourFullTextOutput.cfm?HarbourNR=Abdera.

This article, the first of a projected series, will identify evocative

images and virtual tours of selected ports of the ancient world so as

to facilitate their introduction into the classroom.

|

2 |

| |

|

| Lothal |

|

|

|

|

Sometime after 2400 B.C, one of the greatest port

cities of the ancient world flourished near where the Indus and associated

river systems flowed into the Indian Ocean at a site now called Lothal.

Lothal featured perhaps the world's first tidal dock, which permitted ships

to enter into the dock through a northern inlet channel connected to the

estuary of the river Sabarmati. The closure of the lock gates permitted

the water level to remain high enough to float the ships at the dockyard.

The ships that left from Lothal's 700 foot brick-lined wharf traveled to

destinations as distant as the Sumerian city Ur in the delta of the Tigris

and Euphrates Rivers, though most of their cargoes were sold at or trans-shipped

from ports in the Persian Gulf where they stopped to trade. Arriving ships

often carried Sumerian tools and tin (used in India to make bronze, a process

that also used copper from as far away as Afghanistan). When outgoing ships

arrived at their destinations, the local inhabitants would have rushed to

examine their cargoes, which included cotton fabrics, exceptional manufactures

such as fine-drilled gemstone beaded jewelry and welcome foodstuffs, like

barely and wheat grown in Indus Valley cities and towns, which spread out

north of Lothal along the Indus River and its tributaries. The richness

of these inter-regional and local exchanges has suggested to some that the

concept of center-periphery relations in the ancient world itself needs

further work (see http://www.adventurecorps.com/archaeo/centperiph.html). |

3 |

|

|

|

Today, Lothal lies many dry and desolate miles inland

from the Indian Ocean. Its great dock was buried beneath sand and silt sometime

after 1900. B.C., perhaps due to a possible massive flood around 2200 B.C.

that led to 300 years of slow decline. Eventually, silt covered Lothal as

it did the great cities it served in the hinterland. Research into its ruins

confirms not merely the great uniformity and worth of Harappan urban planning,

but the ingenuity of its people. For a virtual tour of Lothal, with student

exercises, go to http://www.harappa.com/lothal/.

For more information on Indian sea navigation, see http://www.crystalinks.com/indiaships.html.

For India's maritime history, see http://indiannavy.nic.in/maritime_history.htm

and K. S. Behera (ed.), Maritime Heritage of India (1999), which

provides commentary on India's eastern ports. |

4 |

| |

|

| Xel

Ha |

|

|

|

Ever since Hernán Cortés reported

his acquisition of a Mayan map, western scholars have known that Mayans

had port cities, and in great number, as Mayan ports were spaced at a day's

rowing distance apart. Though most of these ports expired after the conquest,

we still know much about them, and in the last two decades they have dramatically

remerged as tourist ports-of-call The Mayan port of Xaman-Ha is now the

tourist Mecca of Playa del Carmen; ancient Pole, with its (once pristine)

underground water-tunnels is now part of the water-park at Xcaret; Zama

is near Tulum (the sea-side later Mayan city depicted in numerous films

such as Against All Odds), and Cozomel was both a trading center

as well a religious center.

|

5 |

One of these ports, Xel-Ha, first served as the

port of the city of Coba in the interior of Yucatan. It is eight miles from

Tulum, a later city which came to control the port. Xel-Ha's beautiful lagoons

may now be over-used by snorklers and divers (including this writer who

has been visiting the region since childhood), but its links with Coba and

Tulum and its own history is only just beginning to be explored.

|

6 |

Coba was established originally as a classic Mayan city

(600-900 A. D.) located about 42 miles west of the later site of Tulum.

It was built between two lakes and is a very large site, encompassing approximately

60 square miles. It was the hub of the largest number of paved roads (16)

in the Mayan world and contains the 138 foot tall post-classic Nahoch

Mul, one of the highest of all Mayan pyramids. Since Xel Ha served so

large a center, it is not surprising that it was itself a large complex:

some argue it covered the largest area of any Mayan city. Its virtually

untouched ruins include a pyramid, palace and associated structures, as

well as what is thought to be a muelle or dock. Its artistic output

included frescos that can still be seen. Pictured below are port buildings,

pyramids, fresco and the lagoon today. Photographs are courtesy of http://www.akumaladventures.com/xelha.html.

|

7 |

|

|

According to legends recounted by local guides,

"the gods were so pleased with their creation that they decided to share

it with man; but declared the iguana (land) and the parrot fish (sea) to

be sacred guardians of Xel-Ha." (See http://fsweb.bainbridge.edu/bdubay/mexico/xel-ha/xel-ha.html).

More reliable is the derivation of its name, which means "place where the

water is born," as the pristine springs that feed the lagoons suggest.

|

8 |

Xel Ha provides an instructor

with an opportunity to develop exercises regarding trade and avoid or supplement

more familiar sites such as Chichen Itza. Such efforts can be facilitated

by exploring Mayan navigation more closely at http://www.mayadiscovery.com/ing/history/default.htm

(scroll down to Mayan Navigators) and http://www.spanishome.com/activities/mayas/trade.htm.

Students can be assigned to examine another site of equal or even surpassing

current interest at Ambergris Caye, which can be explored at http://www.ambergriscaye.com/pages/mayan/earlyhistory.html

and http://www.ambergriscaye.com/pages/mayan/ambergmaya.html.

Books that discuss Mayan trade include Linda Schele and Peter Mathews: The

Code of Kings (1998), Guiseppe

Orefici, Maya (1998), Robert Sharer, The AncientMaya

(1994) and Gene S. Stuart, and George E. Stuart: Lost Kingdoms of the

Maya (1993).

|

9 |

| |

|

| Ostia/Portus |

|

|

|

Ostia, Rome's port city on the Tiber, featured two

harbors. The second, Portus, was built to cope with the rising trade with

Spain and north Africa, which is well known, and also with India, which

trade is lesser known, but was nevertheless quite important during the last

years of the Republic and early decades of the Empire. The use of these

harbors climaxed in the second century A.D. and declined thereafter.

|

10 |

|

|

This site also offers a street-by street reconstruction

of Ostia town and old port (left). See http://www.ostia-antica.org/map/ostia-m.htm

and click on map section.

|

11 |

|

|

Lindsey Davis's novel Scandal Takes a Holiday

(2004) not only includes fully developed maps and cityscape, but illustrates

virtually every socio-political and religious aspects of life in Ostia/Portus

in approximately 76 A.D. The tale is one of the best of the author's series

of stories about a fictional Roman informer, or private detective. As in

most historical novels, there are some anachronisms in speech and character,

but here a close study of Ostia is at center stage: the reader is given

a vivid tour of Ostia's food stalls, temples, police barracks and villas,

as well as insight into its politics from guilds to pirates.

|

12 |

|

The website "Ostia: harbour of Ancient Rome" at

http://www.ostia-antica.org/

offers not only maps and 3-D reconstructions, but a complete illustrated

history (http://www.ostia-antica.org/intro.htm#32)

and primary sources, including remarks on Ostia by dozens of Roman writers,

such as the following from Plutarch at http://www.ostia-antica.org/anctexts.htm:

|

13 |

| |

|

| PLUTARCHUS |

|

| The

Greek author Plutarchus (c. 46-127 AD) was procurator of Achaea under Hadrian.

He is best known for his Parallel Lives, biographies of eminent Greeks and

Romans, composed in pairs. |

|

| |

|

Parallel Lives, Caesar

58, 10

In the midst of the Parthian expedition he was preparing to cut through

the isthmus of Corinth, and had put Anienus in charge of the work. He

also proposed to divert the Tiber immediately below Rome by a deep canal

which was to run round to the Circaean promontory and be led into the

sea at Terracina. By this means he would provide a safe and easy passage

for traders bound for Rome. In addition he proposed to drain the marshes

by Pometia and Setia and so provide productive land for thousands of

men. In the sea nearest Rome he intended to enclose the sea by building

moles, and to dredge the hidden shoals off the coast of Ostia, which

were dangerous. So he would provide harbours and anchorages to match

the great volume of shipping. These schemes were being prepared. [Translation:

R. Meiggs, Roman Ostia, p. 53.]

|

14 |

| |

|

| Carthage |

|

|

|

15 |

The imperial capital's port at Carthage near modern

Tunis is an engineering marvel, one that reminds us that Romans were not

the only advanced technologists of their time. Indeed, the Romans copied

Carthaginian ships in building up their own navy. They later strengthened

this model with Athenian ship designs, an act that demonstrates their early

capacity for synthesis and may serve as another indicating that Greek sculpture

was but one of the many Greek styles which Romans borrowed from their predecessors.

|

16 |

|

| |

|

Aerial

views of the city of Carthage and its port not far from

present day Tunis.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Above,

a cutaway view of the inner harbor, the remains of the

boat ramp and an engraving of J. M. Turner's painting

of Dido building the city and harbor. Below, an artist's

reconstruction of the inner harbor and a replica of the

type of Carthaginian ship captured by the Romans who copied

the design.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Carthaginian Empire's role in shaping the early

Mediterranean world, the nature of its own unique culture and its destruction

by Rome are examined at http://www.livius.org/carthage.html.

This site provides links to articles, biographies and primary sources relating

to Carthaginian history. Other websites providing narrative histories of

the empire or address its trade, economy and technology include http://phoenicia.org/puniceconomy.html

and http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/C/carthage/.

|

17 |

| |

|

| Hepu |

|

|

|

Hepu, like Lothal, was a major port which was lost

for centuries and whose recovery has added much to our understanding of

the place of port cities in world history. Now located within Beihai City

in Hepu county in south China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Hepu has

revealed to archeologists that it was perhaps China's oldest seaport and

thus the oldest port on the Silk Route. Its history also illuminates why

it became "one of the main overseas Chinese hometowns of China."

|

18 |

|

|

According to the Chinese government, archeological

work has recently shown that the site of Hepu was "the oldest departure

point on the country's ancient maritime trading route." This status was

spurred by its role as a transportation hub: as a water port, it served

as the "main gate" for the "Silk Road on the sea," while a secondary

channel via the Western River tied Hepu to Wuzhou and Guangzhou. Hepu was

also connected to Indochina generally by sea, while a southwestern mountainous

route connected it to northern Vietnam.

|

19 |

|

Records suggest that, in keeping with the Han expansionist

policy, Hepu was integrated into the empire in 111 B.C. when Lianzhou Town

at Hepu became a three-tiered local administrative seat. The ruins of Hepu

port appear to date from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 A.D.). The

city was walled and surrounded by a moat and was prosperous enough to be

the site of Han tombs. Funerary objects and pottery pieces that have been

excavated date from as late as 220 A.D. They include "imported jewelry and

utensils fashioned from such materials as colored glazed pottery, amber,

agate and crystal" suggesting the city's role as a major trading port. Researcher

Xiong Zhaoming remarked that "The gentle slope between the moat and

the city walls means such works were not meant for defense, but served as

a symbol and for trading convenience." (See http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/55/747.html.) |

20 |

| |

21 |

|

As Hepu grew in importance, some traders immigrated

from Guangxi to Yanluo or other places in the Western Han dynasty, a process

which continued apace under successive dynasties, particularly during the

outward looking years of the Ming. Many immigrated "to Vietnam, Thailand,

Malaya and other south Asia countries." When the Taiping Uprising failed,

"the farmer uprising army couldn't find a foothold in China, and they had

to escape successively to Vietnam, Malaya and other places, and the amount

was more than 10 thousand." From records at Hepu and elsewhere, it appeared

that such migrations occurred frequently as a result of failed uprisings.

In 1679, many Ming dynasty leaders in the south refused to surrender to

the Qing dynasty and boarded "over 50 warships and more than 3000 subordinations

to flee from the coastal area of Guangxi to Kampuchea (which then encompassed

the Mekong delta)." After the end of the Opium War, many southern Chinese

laborers were purchased or recruited by the Western nations who shipped

them throughout Asia and Africa. In the years 1900 to 1911, over 20 thousand

local workers were dispatched in this manner. Speeding this process was

Chinese oppression of the ethnic minorities that populated the region. According

to contemporary Chinese authorities, who rarely miss so rich an opportunity

to condemn the "feudal" regimes of the past, "in Ming times many Zhuang,

Dai, Nong, Miao and Yao minorities in Southwest and Northwest zone of Guangxi

migrated to Burma, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam." They are also careful to

note the leading roles of Chinese ex-patriots from this region who fought

the spread of Western imperialism from the Red River to Cuba and the essential

role played by their descendants in sending remittances that are helping

to drive south China's remarkable economic growth (see the brief history

and statistical data offered at http://www.gxi.gov.cn/English/overseas%20Chinese/survey%20of%20overseas%20chinese.htm).

For other forces driving Chinese out-migration,

especially in the south, see http://www.anu.edu.au/asianstudies/decrespigny/south_china.html.

|

22 |

| |

|

| Conclusion |

|

|

The study of ancient port cities reminds us of the

great continuity of patterns of global interaction. The exchange of goods

between civilizations and coastal/hinterland relations, and advances in

engineering fostering that exchange via efficient dock-building and navigation,

seem to be part of a pattern as old as Sumer and as familiar as containerization.

The ships from Hepu that carried poor and powerless Chinese to a life of

hard labor around the globe should call to mind the ships that much later

were to carry Irish immigrants to America: politics, not merely famine,

played a factor in both events. Sumer's trade in tools for both luxury goods

and foodstuffs with India remind us of that interdependence is not a product

of modern globalization, while Mayan trade patterns leave no doubt that

this was true of world's both old and new. This essay was written in the

hope that instructors might profit from drawing attention to these continuities.

Student can easy follow up the sources cited to explore them in more detail,

perhaps by employing them on scavenger hunts for trade items, or for the

identification and further analysis of ancient trade emporiums including

and beyond those suggested above, such as Athens/Piraeus, Caesarea, Londinium,

etc. A list of many of these ports offering links to each can be found at

http://www.abc.se/~m10354/uwa/harbours.htm.

The modern world economy may, as suggested by Ken Pomerantz and Steve Topik

(The World that Trade Created: Culture, Society and the World Economy,

1400 to the Present, 2000), have been one shaped by international trade,

but ancient global ports of call indicate that our predecessors were no

less concerned with, and effected by, economies well beyond their horizon.

|

23 |

| Biographical

Note: Marc Jason Gilbert is Professor of History at North Georgia

College and State University, and is a University System of Georgia Regents

Distinguished Professor of Teaching and Learning. He is also co-director

of the University System of Georgia's programs in India and Vietnam. He

has published several books about Vietnam, and is co-author with Peter Stearns,

Michael Adas and Stuart Schwartz of the third revised edition of the

world history survey text, World Civilizations: The Global Experience

(2000). |

24 |